Advertisement

2 Afghan families still living in a Newburyport church basement after more than a year

Play

When two large families that had fled Afghanistan moved into the basement of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Newburyport just over a year ago, there were 15 kids between two sets of parents. Today they're still living in the church, and there's a 16th child.

Nadya was born three months ago, making her the only U.S. citizen in the two families.

Advocates helping them say the fact that they haven't found permanent housing shows there aren't sufficient systems in place to help them build a life here.

The families in the church basement are among more than 120,000 Afghan citizens the U.S. evacuated from Afghanistan in August of 2021, when American troops finished withdrawing from that country and the Taliban seized control. More than 88,000 came to the U.S., which had pledged to help Afghans who had worked for the Afghan or U.S. governments — including in joint military efforts — and were now in danger from the Taliban.

More than 2,000 of the Afghan evacuees came to Massachusetts, according to state officials. Forty ended up in the small, affluent city of Newburyport.

Adjusting to a new life while welcoming a new baby

On a recent day, Nadya’s mom, Gulalai, cradled her, sitting on a bed in the room her eight other children share in the church basement. The baby was dressed in a onesie and knit cap church members donated. Her siblings clambered around and leaned over to kiss her head.

Nadya was born with a developmental disorder , and Gulalai worries about the child's future. Her other kids have adjusted well to life in Newburyport, for the most part.

"They're all doing great. They like school... I'm happy for them," Gulalai said through an interpreter. "But since we're living in just a few rooms ... the basement is so tight for us with these big families living here with all the kids, so that makes it a bit difficult for us."

The families use one room as a den, where the kids watch cartoons and play.

Benafsha, 20, looks after her younger siblings. She wishes her family had its own place to call home. But she’s started to put down roots in the community. She attends Newburyport High School, has friends and loves going to the beach.

"When I see the beach, and I'm so happy, I say, 'Oh, here it's very big,' " Benafsha said.

Her two teenaged brothers are settling in, as well. They have after-school jobs at the local Market Basket.

Working but can't afford a home here

Their father, Sami, has also found a job. (WBUR has agreed not to use the family's last name because Sami was in the Afghan military and still fears being targeted by the Taliban.) He does landscaping, repairs and painting for a local handyman. On the day we visited, he was raking and blowing leaves at a home on the waterfront.

He's grateful for the job and the pay. He has to support his wife and children here in Newburyport, and his parents and siblings in Afghanistan.

Sami and his family also received one-time payments from the state and federal governments when they arrived — $3,500 for each Afghan evacuee, adding up to $35,000 for the family. They get transitional cash and food assistance from the state, too, according to the resettlement agency that's helped them.

But even with the job and the aid, the price of housing here is beyond Sami’s reach.

"It's not possible for me to find a house or rent a house," he said through a translator. "I hear people saying there are families that are eligible for low-income houses. Hopefully, if someone helps me, that would be a good way to go — to move there."

But in Massachusetts, there are years-long waitlists for subsidized housing. Most deeded affordable housing isn't big enough to accommodate very large families; and there’s very little of it in Newburyport, according to the state.

"And so what has become clear is that ... if it doesn't exist, we have to create it," said Rev. Jarred Mercer, rector at St. Paul’s.

In the past year, Mercer has had to assume the role of housing advocate. He's worked with local nonprofit and city leaders to brainstorm ways to find the Afghan families stable, permanent housing. In addition to the two families living in his church, a family of 11 Afghan evacuees is staying at the Unitarian church in Newburyport. Two smaller families got apartments in town — one of them after living temporarily in a different church.

The churches have raised enough money to put down payments on one or two homes for the Afghan evacuees, but the families wouldn't be able to afford the mortgage payments.

"What we've wanted to do — have been working on doing — is establishing permanent resettlement homes for displaced people that would serve these five families now, but hopefully 50 or 100 years from now, others coming in, as well," Mercer said.

And those families will be coming. A record number of people are being forced to flee their homes worldwide because of war, human rights violations and climate change.

Approximately 5,000 refugees and other immigrants who receive federal assistance came to Massachusetts in the past two years, according to data provided by the state Office of Refugees and Immigrants. The largest groups were from Afghanistan, Haiti and Ukraine.

Pushing for new housing resources

Mercer thinks the government needs to establish new housing subsidies specifically to help forcibly displaced people. That way, they wouldn't vie for the same resources as others in need. Those subsidies could help an affordable housing program operate so-called resettlement homes, help people rent those properties, or help refugees or other forcibly displaced people rent units from other landlords.

Mercer and other advocates have raised the idea with state and federal officials, but so far no new pathways to housing have been developed.

Anca Moraru is among those other advocates. She’s chief program officer with the refugee resettlement agency International Institute of New England.

For the 544 other Afghan evacuees it's assisting, the agency quickly found housing in cities including New Bedford, Lowell and Manchester, New Hampshire, according to Moraru. But close to one-third of them were single men, and the average size of the families was five people. Still, housing them quickly was only possible because property owners offered to rent to Afghans at discounted rates, Moraru said. It’s even tougher to get housing for refugees from other places.

“I think we do need maybe a state plan — some kind of housing plan for displaced people," she said. "We are receiving so many people, and we can’t just struggle to find housing every day … So we need a separate funding pool.”

The Massachusetts Department of Housing and Community Development said it already has programs developers and advocates can tap into to create affordable housing in Newburyport. (Nonprofits and developers have previously used those programs to create some affordable units in the city.) And they could develop housing dedicated to forcibly displaced people — as long as it complies with fair housing laws.

But that kind of project would take years, Mercer said, and the Afghan families living in his church’s basement need solutions now.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development told WBUR that although the department doesn't have any separate funding stream for housing refugees and other forcibly displaced people at this time, HUD "continues to explore ways to address the lack of affordable housing we are seeing among refugee and other populations across the country."

Meanwhile, Newburyport officials are looking for parcels in the city where advocates could build homes for the Afghans, which could be used by other displaced people in the future.

“Part of what we're talking about are partial solutions," said Geordie Vining, senior project manager in Newburyport's planning and development office. "They're not comprehensive solutions in terms of being able to address housing for all of these families."

Vining said he personally sees the housing crisis faced by the Afghan families as a failure at the federal level.

"This is a problem that stems from the country's involvement in Afghanistan ... the somewhat chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan," he said. "It is a great big void that we've been trying to step into and trying to figure out — a small community working with small local churches, as opposed to these larger governmental agencies."

Sean Reardon took office as Newburyport mayor a year ago, as the Afghan evacuees were arriving in the city of just 18,000 people.

"I think we've just been so happy to have them here," Reardon said.

Asked if he thinks the city and the Afghan families would have been better served if they had been located elsewhere, Reardon said he doesn't think so.

"There are certainly challenges. And we've had those conversations, even recently, with the group," Reardon said. "And the families were adamant that they just are so thankful to be here and … They've just added so much already, I think, to the community."

The community wants the families to be able to stay, according to Mercer.

"Thousands of people are connected to them in some way through school or work or friendships or whatever, and people care about them. And I think what it means to live in Newburyport has changed for people in the past year and that this is a part of who we are," he said.

Mercer's dream is that someone donates a large house, or several million dollars, to build homes for all of the families. For now, he said, he’s frustrated that he has to be a constant agitator on the issue of creating new housing solutions.

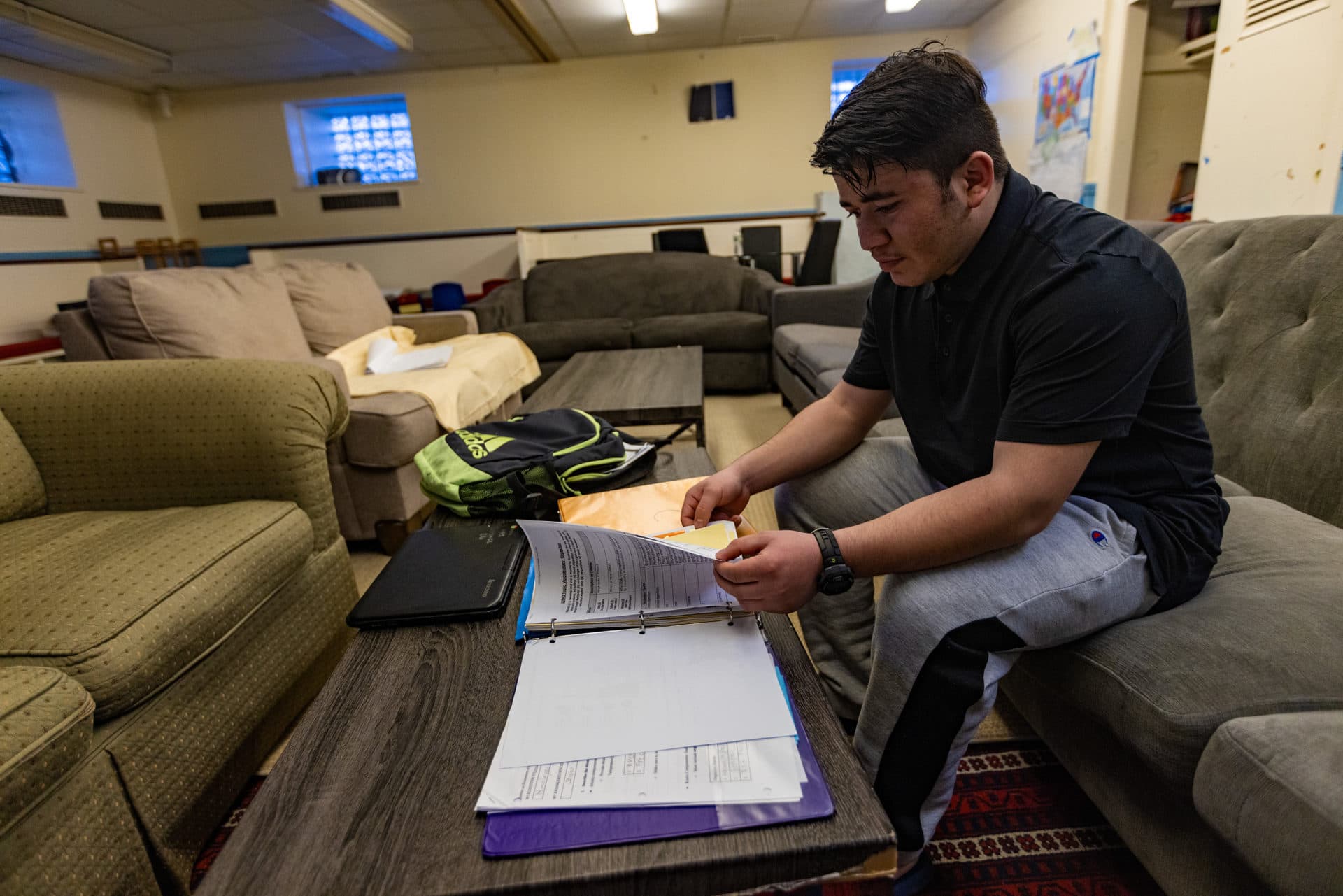

Meanwhile, in a room with couches and coffee tables in the St. Paul’s basement, 18-year-old Afzal just finished his homework. He said, through an interpreter, that he’s proud of what he’s accomplishing here — he’s attending high school, working at the grocery store and earning money for his family. But after a year living in the church, he feels in limbo.

"We're still thinking we didn't reach America yet. We're on the way," Afzal said. "If we find our own home and we have a house, then we'll be relaxed that we reached our home and now our life can start."

This segment aired on February 2, 2023.