Advertisement

Author Tracy Kidder profiles Boston's doctor to the homeless community, Jim O'Connell

Play

Don't try calling Jim O'Connell a saint. He's quick to reject the name "Saint Jim" that some in Boston have given him. But to thousands of people who are homeless in the city, he's a savior on the street.

O'Connell is a doctor. He studied and trained at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, and was in line for a coveted fellowship in 1985 when he took a detour. Boston had won some grant money to start a health care program for people who were homeless, and O'Connell was asked to help build it as its first doctor.

Some nurses had already been running a health clinic at Pine Street Inn, the large homeless shelter in Boston, for years when O'Connell showed up. The nurses set him straight on day one. They told him to put away his stethoscope, slow down and spend time talking with his patients, he recalled.

O'Connell thought he'd only do it for a year. But almost four decades later he's still at it. And the organization, for which he's both the founding physician and president, Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program , is held up as a national model for the delivery of comprehensive medical care to the homeless community.

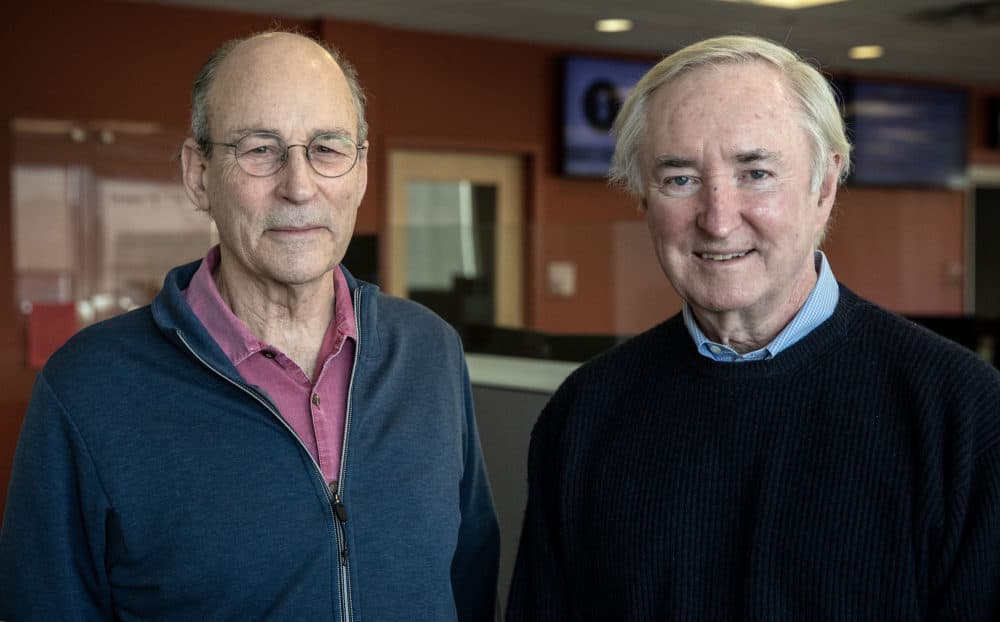

The stories of the revered doctor and the organization's approach to health care are chronicled in a new book by Pulitzer Prize-winning author Tracy Kidder. He shadowed O'Connell for five years to write the book, called " Rough Sleepers. " That's an old British term for people who live on the street.

O'Connell and his team expanded the program to other shelters and hospital-based clinics. They opened the nation's first medical respite facility for people experiencing homelessness and a headquarters with primary medical and mental health care, substance use treatment and a dental clinic. The program serves about 10,000 people a year — even those who find permanent housing.

"We think of ourselves, primarily, as, like, old-time country doctors working in a very urban setting, O'Connell said. "It's bringing the best in medicine to some of the people who've been left most excluded. ... As you get to know them, where they live, what they're struggling with, what their stories are, and they get to know you — it's a two way street here — there's something about the dialogue and the relationship that happens there. ... You get swallowed, in a way, by it."

"And the people you are serving really, really need those skills that you've learned. And they're really grateful for it," Kidder said. "What you're really doing is — I'm not sure you're supposed to use this term anymore — is practicing medicine in the world's richest country, but the Third World part. It's a part of the country that many people don't even want to imagine exists here."

In the book, Kidder writes about one of O'Connell's first tasks as a doctor to the homeless community: soaking the feet of shelter guests, as the nurses directed him to do:

Foot soaking in a homeless shelter — the biblical connotations were obvious. But for Jim, what counted most were the practical lessons, the way this simple therapy reversed the usual order — placing the doctor at the foot of the people he was trying to serve. As a doctor in training, he'd spent most of his time telling patients what he thought, saying, 'We need to get that blood pressure down,' or, 'I'm concerned about the results of your kidney tests.' This new approach was entirely different, and, he began to realize, it was much more effective clinically, at least with homeless people. And foot soaking was the perfect way to begin.

Kidder and O'Connell spoke with WBUR's All Things Considered host Lisa Mullins.

Highlights from this interview have been lightly edited for clarity.

Interview Highlights

On soaking the feet of people who were homeless:

Jim O'Connell : "I think real honestly, I was overwhelmed and kind of discouraged that I had chosen the wrong way to spend my year. And soaking feet is pretty smelly. And, you know, there's a lot in it. But I kept watching the nurses doing it so devotedly. And as I took care of more people ... there's something about being at the foot of the person you're serving. You're out of their personal space. It's something very soothing for them. And we started to realize that caring for the feet is kind of an entry into the soul.

"There's a man I had seen in the emergency room at Mass General dozens and dozens of times, and he suffered from a pretty terrible paranoid schizophrenia. He had terribly swollen feet. So we actually needed two buckets — one for each foot, rather than one [for both feet]. And he, you know, just didn't say anything to me for about a month.

"And then finally, after about six weeks, he looked down to me and he said, 'Hey, I thought you were supposed to be a doctor.' And it was, like, the first person in the clinic that acknowledged I was a doctor, right? And I lit up, and I said, 'Yeah, I am.' And he said, 'What the hell are you doing soaking feet?' And I said, 'You know, I don't really know, but I'm doing whatever the nurses tell me to do.' And... he looked at me and said, 'You're a smart man. I do the same thing.'

"And then a week or two later, he asked me for some medicine to help him sleep. And that was the beginning of a pathway to get him on all the medicines that we had spent, literally, 25 years at Mass General saying he was utterly resistant to take."

On meeting people where they are — bringing health care to them on the streets:

O'Connell : "I think the first principle that we learned is that we couldn't sit in our clinics and wait for people to come to us. We had to go to wherever they were. ... I had to learn to do all the things that I think, professionally, we didn't do because they were kind of boundary issues. Have coffee with people, listen to them and talk to them about yourself. ... I spent a lot of years bartending. It reminded me of being a bartender... So this was the first opportunity I had where we [could] just follow people wherever they were. Go sit on a park bench with them. Most people, you know, have amazing stories to tell and are anxious to tell [them], but only if they feel safe. And so our job was to make them feel safe."

Tracy Kidder : "I have a quick way to summarize this that Jim told me, actually. He said, you know, 'In medical school, we were taught to be friendly but not a friend.' And then he added, 'But if we took that approach with this population, this homeless population, we would get nowhere.' So a system of friends is really what they've developed. It's quite remarkable."

On O'Connell not being able to make everything right for his patients, much as he could not fix things for his mother, who suffered from bipolar disorder and spent time in hospitals when he was growing up:

O'Connell : "I can think of two women that we saw in the van the other night who have both been sleeping on the streets for 35 to 38 years, despite everything we're doing. And I keep thinking, if that was my mother, you know, what would I do?

"... I do know that we rarely give up on anyone and that we've had a long enough history of caring for folks that we realize that it takes time, and that some people will fire us and then come back, and fire us again and then come back. There was a cardinal rule that I've [shared] with all of our staff, [which] is that you can never take anything [our patients] say personally. If you take it personally, it becomes really soul wrenching.

"We have one man that Tracy has seen with me often, who is a real character. He comes storming into the clinic, usually gets right in your face and says something outrageous, and then you have to work with him to calm him down. And he'll be calm for a few minutes and then fly up off the chair and start yelling again. And for some of the staff ... he would say things that would make the staff want to kick him out of the hospital.

"And then we'd have to calm everybody down and try to say, 'No, this is who he is, but he's not going to hurt you, and we're going to have to work on that.' So it was [that] knowing who he was and watching him for years let you have a much better sense of what's going on. It also gives us a much better sense when somebody is really out of control."

Kidder : "Jim doesn't lose his temper, which is quite remarkable to me because I lose mine all the time, even at my advanced age. You can sum up all of this in that great line from [philosopher Jean-Jacques] Rousseau, which is, you know, 'What wisdom can you find that is greater than kindness?' It works. It really works, even with people who are really floridly demented, I think. I've seen it work."

O'Connell : "Some of that anger ... it's on us. You know, it's ... whatever they didn't get in school, or whatever they didn't get at home, or whatever happened to them from the trauma [of their childhood], the anger for that is really what we're seeing. It's not at any of us. It's at the system and the structural things that put them there."

On dealing with frustrations over governments' and society's response to homelessness:

O'Connell : "I think we learned a long time ago that our job, our niche, was to provide the best care we could to people who are experiencing homelessness or had been homeless a long time and were now in housing. And then you start to realize that as a doctor and as a nurse, we can take care of people, but we're not really good at changing society — and that if we worry about that, it burns us out in a hurry. So we had to learn to let some of that go.

"Now, the other side of that is we work in a city that has been incredibly kind to homeless people. The mayors, all of the mayors since I've been starting ... and the city has been incredibly creative in coming up with the housing that it can do. I think everybody acknowledges to scale it to what we need is still a long way to go. ... Somebody's got to really tackle this major problem of how do you get enough housing with enough support ... that people need to stay fundamentally in housing."

This segment aired on January 17, 2023.