Advertisement

Commentary

That night, I saw my boy again

We are with the boys who are the boys that our son Jesse would never have been. But they are 17, the same age as he was the year he died, and there is something that brings to mind our son — so different in body, so alike in the yearning, the curiosity, the talent, the vulnerability these boys wear like an upturned collar on a favorite shirt.

My husband and I are judging these boys. Our friends, the parents of one of the boys, have asked us to watch the scenes and monologues they have chosen to perform for a national competition.

We sit in our friends’ comfortable living room and are introduced to the boys, who are all polite and wary. We meet their teacher, too, a Catholic brother. My husband side-eyes me nervously and wonders if I’ll launch into a tirade about my years as a parochial school student suffering the tender mercies of the sisters of St. Joseph, a favorite rant of mine at dinner parties and in print.

The boys in turn side-eye my husband, probably thinking about his Academy award and wondering what he’ll have to say about them.

But I am remembering Jesse, who arrived 10 weeks early on a chaotic day filled with confusion and fear. He was born in a Catholic hospital, St. Vincent’s in Greenwich Village. Statues of saints lined the halls, their impassive faces offering a cold sort of mute succor, but I knew even in the dire aftermath of his birth — when Jesse’s life was connected to a serpent’s nest of tubes — that he would never be baptized in the Catholic Church.

His pure light shone through the opaque plastic of his enchanted prince isolette. I wanted to spit at the thought of some priest removing the church’s arcane notion of an original sin from my son’s pure, incandescent being.

I don’t think of Jesse’s first fraught birthday, the icy fear, the grim pronouncements. Now I remember his later birthdays, sunny still-warm October days on our deck, my son encircled by cousins and friends, laughter and cake, the surrounding marsh in hues of gold. I want to find the multiverse where this day exists and reside there forever.

When the need for palliative spiritual care overwhelms me, I study quantum physics, the secular religion for the grieving unbeliever, and try to understand. I no longer pray to a father god or make the sign of the cross. A religion that eradicates the mother won’t give me back my son. But in our friends’ living room, I bypass these anticlerical thoughts. I’m not here for religious debate with the Catholic brother, who seems very sweet; tonight, we’re audience and mentors to the boys.

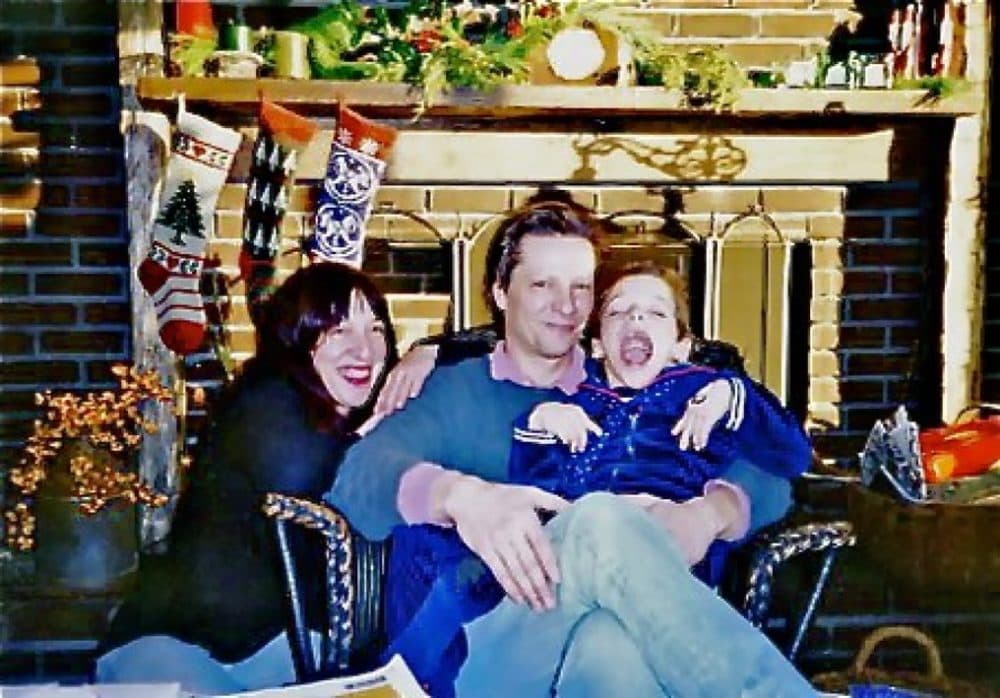

Jesse had cerebral palsy. He wrote poetry on his computer, each word a hard-won victory over his wavering, disobedient hands and flyaway arms. “I am sometimes invisible,” was placed dead center in one of his poems, at his insistence.

I am sometimes invisible.

He was aware of the struggle to make his mark on his world. And he never stopped trying to use his voice: not the teenage croak of his last years, but the one that appeared in pixels on the page.

But these vibrant, eager boys — so present in the world Jess has left behind forever.

If he were sitting in this cozy room, in his wheelchair, how would they relate to him? Jesse’s friends were into theatre and writing. I pictured Jesse writing a scene for one of these kids. I saw him, his spiky hair, his long, furled fingers grasping the pull switch on his specially outfitted computer as he chose or rejected words. I imagined him watching as the boys spoke the words he wrote but could not say, except through a device.

The first scene we observed was a two-hander about a pair of brothers, one of them autistic. I braced myself for either a treacly or ableist presentation, but the boys performed a sensitive and believable dramatic scene, imaginatively blocked and well-acted. The rest of the boys followed, some in pairs, some performing monologues. We gave feedback and asked questions about intent and preparation.

They stood in the living room, thanking us. I swallowed my thanks, knowing they wouldn’t understand how grateful I was for the gift they had given, how their shaky, truth-seeking light had, for a moment, re-illuminated my son’s luster here on earth.