Advertisement

Community Colleges Ask For Help As Enrollment Continues To Drop

Play

Massachusetts’ 15 community colleges had already hit a rough patch before 2020. Enrollment and tuition revenue had been falling for nearly a decade, while costs rose.

Then the pandemic struck. Now, facing an urgent double crisis of public health and economics, community colleges are sounding the alarm — and asking for help.

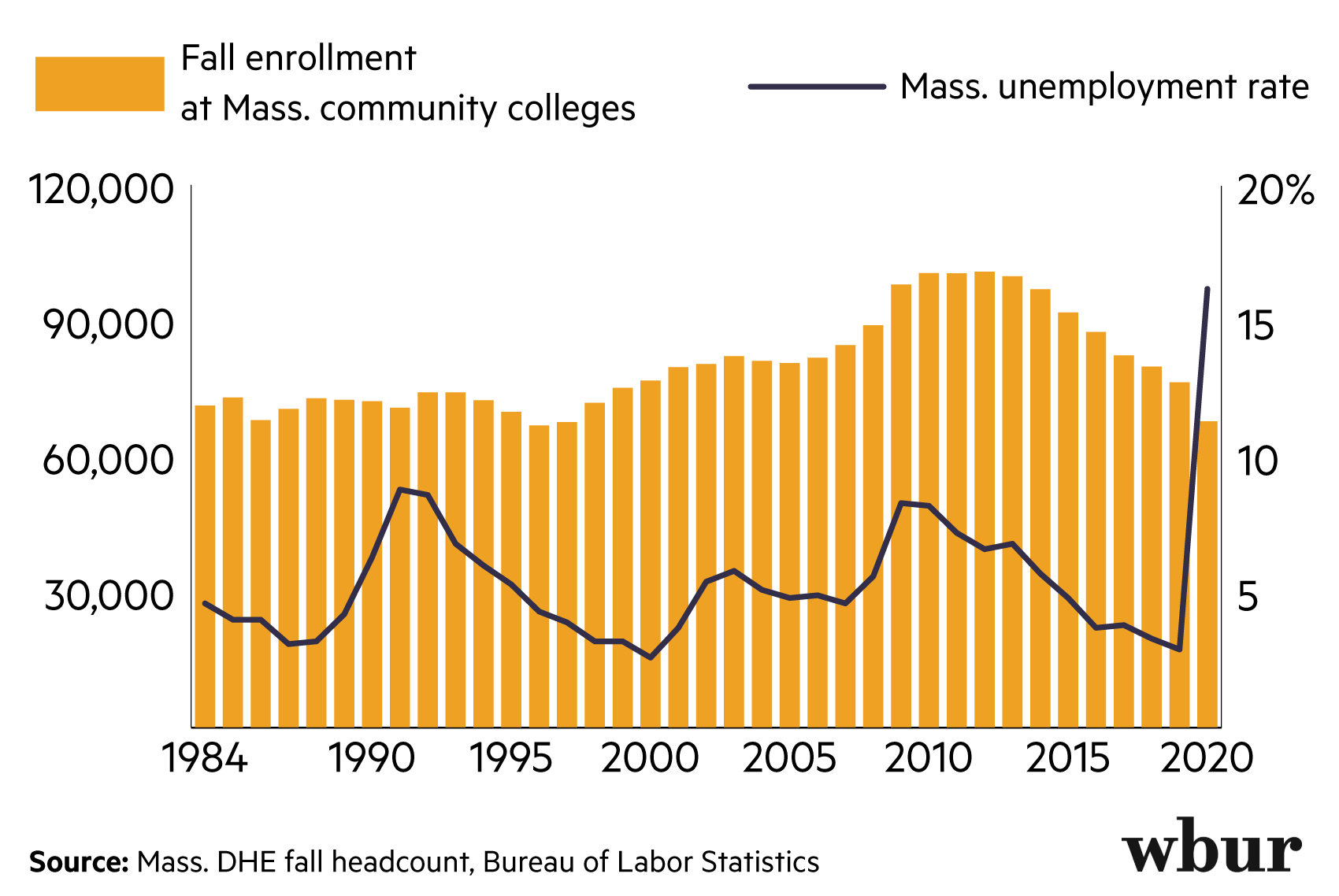

It’s a strange departure for the colleges, which have historically thrived during recessions. Their campuses still tend to be the most accessible start to retraining while juggling job searches, part-time work and family obligations.

Not this time. Community college enrollment crashed to a 23-year low in the fall of 2020, and the early data suggest that next fall could be even worse. Those colleges themselves will need to recover if they hope to play the hoped-for role in the state’s way back from the latest economic crisis.

“So Much Uncertainty”

Cameron Costa serves as evidence that community colleges can and do still fulfill their mission, even under the stresses of the present moment.

Costa is the son of a single mother who moved from Charlotte, N.C., back to New Bedford in 2005: in part to be near family, but also to take advantage of Massachusetts’ system of public education. He graduated from Bristol Community College in December, and is now studying management at UMass Dartmouth.

Though he was only there for a year and a half, Costa said Bristol Community College was a key stepping-stone. For him and his peers, “college in itself is just scary.”

“A first-generation, Latinx student — who doesn’t have a strong support system at home, who was told not to even go to college because it’s a waste of time — how likely are they to go to the dean of enrollment [if they have a problem]?,” Costa asked. “Not likely.”

Costa said he relied on his mother’s encouragement — and a few key mentors at Bristol — to make it through.

But Costa understands why many similar students stall in college — or just never enroll. They find the term of student loans difficult to understand, or just difficult to pay. And he says there’s often too little assurance of a better job waiting on the other end of an associate’s degree.

While students surged into community colleges after the 2008 financial crash, they have been drifting away for six years now — and enrollment plummeted by 11% this past fall. The drop was especially acute among new students; the colleges enrolled 26% fewer of those than they did last year.

“They tell us that they’re out of work, they’re broke, they’re worried about food, they’re worried about housing, and about taking care of their families.”

Jim Mabry, president of Middlesex Community College, on what his staff is hearing from withdrawing students

State Commissioner of Higher Education Carlos Santiago and his team took some comfort from the fact that students who were already enrolled didn’t step away in such great proportions. And they have some preliminary explanations for the wider drop.

Community colleges tend to draw on the communities that were hardest-hit by the virus. Not only had students lost or come to worry about their part- or full-time jobs, “they probably have family members that have died, or contracted serious illness,” Santiago said. “They’re clearly reluctant to bring [additional health risks] into their families, and going to school may exacerbate that.”

The paperwork of getting into and paying for college may seem like too much to deal with at the moment. Mass. students submitted far fewer FAFSAs — applications for federal student aid — last year, especially after the pandemic’s effects became clear. The current FAFSA cycle will continue running for a few more months, but so far it doesn’t look good: about 16% behind last year’s pace.

At Middlesex Community College, fall enrollment has declined by nearly 30% since 2013, with a third of that drop in the past year. “We’ve been actively reaching out to students: ‘Why aren’t you coming back?’,” said college president Jim Mabry. “They tell us that they’re out of work, they’re broke, they’re worried about food, they’re worried about housing, and about taking care of their families.”

Those problems of poverty, painful before, are acute now. But Santiago resisted the idea that low-income families no longer see the value of higher education.

“I don’t fully believe that,” he said. “If you go to a Latino household, they understand the value — that it’s a means to social and economic mobility. The difference is the hurdles they face, the lack of resources… keep them from fully taking advantage.”

“It’s Just Not Fair”

One of Cameron Costa’s most cherished mentors at BCC was Amy Blanchette, who had graduated from the college herself in 2017 and joined its department of student and family engagement on a part-time basis.

Blanchette and her colleagues were there to take the fear out of college for working-class students: tracking deadlines, running food banks, steering students toward affordable housing or financial aid.

But Blanchette says small cuts mounted over six years. The college’s latest report, from 2018, showed 120 staff were cut between 2015 and 2018. Blanchette says she saw work-study positions in her office dry up, while the campus library’s hours were abbreviated.

Then, last May, Blanchette herself was laid off, along with over 130 others. In a letter to the community, college president Laura Douglas wrote that the layoffs were due to the “unprecedented financial position” created by the pandemic, and that the college hoped to reinstate workers once it subsides.

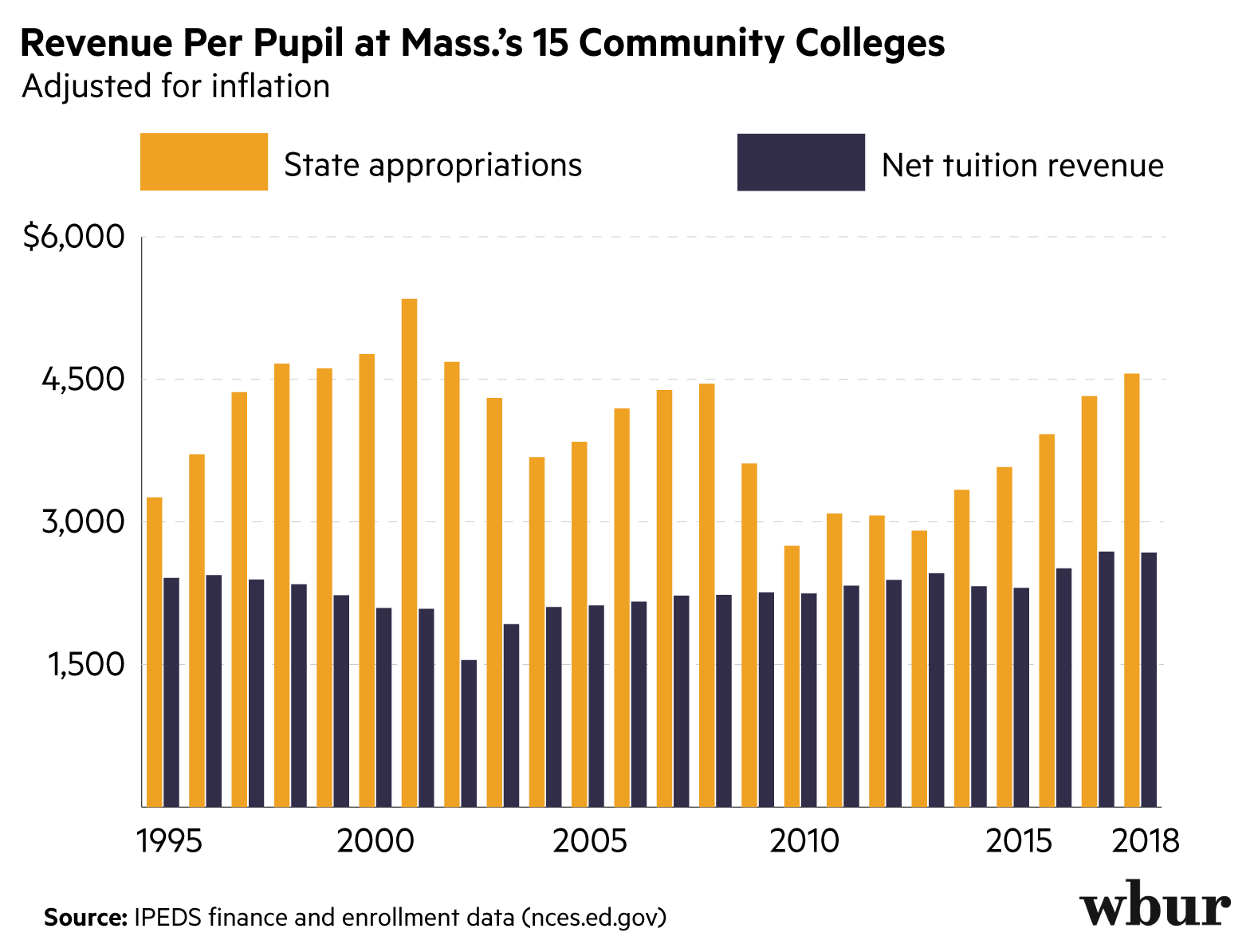

Nine months later, Blanchette is still looking for work. “What gets me is that students are paying more and more every year in tuition and fees, and they’re not getting the same amount of service,” she said. “It’s just not fair.”

Blanchette is president of the board of PHENOM, the Public Higher Education Network of Massachusetts, which advocates for state investment in public colleges and universities. She encouraged Costa to join as treasurer. (Both are volunteer positions.)

The average net price across all Massachusetts community colleges — what students pay to attend, after financial aid — climbed by 23% between 2009 and 2018. (The cost of attending Bristol Community College has climbed, too, but remains relatively low: around $6,700 as of 2018.)Santiago acknowledged what he called a “real resource issue” facing community colleges in particular.

Annual state support for the colleges has been climbing since 2014 — but, when adjusted for inflation, it still hasn’t recovered to where it was in 2001. Santiago said again that the state must consider ways to increase overall funding of public higher education, as well as at its distribution.

He said that ”the bulk of students most in need” are at community colleges and state universities — and that more of the overall spending on the sector might flow from well-heeled UMass in their direction: “We need to be a bit more equitable.”

Jim Mabry said money is certainly a serious obstacle on his campus, and that any further cuts could be almost incapacitating.

Mabry argued that community-college tuition — while still markedly cheaper than it is at four-year universities — is “very high” by national standards, with credit cost per hour ranging to $230 and above, while in other states — including California, New Mexico and Texas — the cost remains below $100.

What’s Next?

Santiago, along with college presidents like Mabry, looks with hope to the “Student SUCCESS Fund,” a line item added to last year’s budget to invest in student supports, like hiring caseworkers to work with stressed-out students: reminding them of deadlines, answering questions and giving encouragement.

Gov. Charlie Baker has proposed using the initial investment of $7 million across two years. A spokesperson with the Executive Office of Education said that slower rollout would help colleges and the state collaborate on programs that work. The Massachusetts Association of Community Colleges plans to lobby in favor of doubling down on the investment in the fiscal year ahead.

There is hope, too, that change in the federal government could bring relief for community colleges as a sector — one that is ailing nationwide, though Santiago said Massachusetts’ enrollment numbers “does not fare very well” by comparison to other states.

First Lady Jill Biden’s decades of service as a community college professor seemed to shape the new president’s education platform , which promises debt-free attendance at those colleges, support beyond Pell grants, and a $50 billion investment in workforce development.

But Mabry, at least, is not pinning all his hopes on the slow-moving machinery of the U.S. Congress. While aid would be nice, “I don’t think it’s going to be that dramatic,” he said.

Instead, he hopes the state itself comes to see the value of these small public colleges, which — if properly cared for — have a vital role to play in training a diverse pool of workers that will be sorely needed.“Before the pandemic, the limiting factor for the [state’s] economy was the workforce. It was really tight; employers were really struggling to find qualified workers,” Mabry said.

“If we want to get this economy going again — not just tomorrow, but over the long term — we need a highly-educated workforce. From a pure economic standpoint, it's absolutely clear.”

This segment aired on February 12, 2021.