Advertisement

Pottery exhibit at the MFA spins a tale of artistry despite the odds

When we think about slavery in the American South, we often think of enslaved Blacks toiling away in cotton or tobacco fields. We generally don’t think of pottery. But, in fact, enslaved African Americans were used to make pottery, and lots of it. Their wares — churns, storage jars, pitchers, bowls, jugs — were produced on an industrial scale in the years leading up to the Civil War. Much of this stoneware originated from a rural area of central South Carolina known as the Old Edgefield District.

In “ Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield South Carolina ,” opening March 4 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, we are provided with an introduction to Edgefield pottery and an often-overlooked aspect of the American slavery system. Although many of us may not know it, hundreds of enslaved African Americans worked in ceramic factories in Edgefield County, South Carolina, producing tens of thousands of pieces of pottery that were sold throughout the country.

Within the brutal barbarity of slavery, and despite harsh conditions and back-breaking labor, enslaved artisans managed to create objects that were not only utilitarian kitchen necessities — the Tupperware of their day — but also objects of superior craftsmanship, notable artistry and even transcendent beauty.

“This is a story about American slavery that isn't often told,” says Jason Young, associate professor of history at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, who co-curated the exhibit with Ethan Lasser, chair of the Art of the Americas at the MFA and Adrienne Spinozzi, associate curator in the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

“ Here is an example of people who are engaged in a thoroughly industrial level of production, and it requires a range of different labor skills, but also intellectual skills and expertise.”

Edgefield pottery of the era was alkaline-glazed stoneware, which was sturdy, durable and relatively low-cost. It has a distinctive earthy look — buttery browns, tawny tans and sepia tones — a result of the red clay and white kaolin deposits found in the area. Some crockery is plain and unadorned while other pieces are festooned with images of figures, flowers or painted swags.

Some of the largest monumental Edgefield pots were the handiwork of one enslaved potter and poet named David Drake, best known simply as “Dave,” the way he signed many of his pieces. Dave’s pots were especially prized, not only for their fine craftsmanship, but also for the poetry verses he would sometimes inscribe on their sides. His work, along with other vessels coming out of slave production, were the final result of an arduous process that began when the enslaved mined the clay, then cut trees to produce the massive amounts of firewood needed to feed kilns, then continued when they threw pots at the potter’s wheel before launching into the final step of firing the work in the kiln. Stoneware was particularly durable because the ceramic pieces were fired at very high temperatures for long periods of time. That may explain why many large pieces that were used in kitchens and smokehouses for food storage still survive today.

These were primarily functional objects, so beauty may not have been at the top of mind for those behind the pottery wheel. And yet, says Lasser, the objects “move into something much bigger as personal expressions. And if that's what we think art is, if it's an expression of humanity, then these pots are that in every way.”

Of the nearly 60 Edgefield pieces included in the show, many never before seen outside the South, there are 19 “face vessels” made by enslaved potters for their own personal use. These are jugs and pitchers in which faces emerge —nose, ears, eyes and sometimes teeth bared in either happiness or anger.

" They started as small thrown vessels made on a wheel,” explains Spinozzi. “And then in the hands of the makers, they turn into something completely different.”

The face vessels may have been inspired by ritualistic masks potters may have known back in their native West Africa. They are revealing, says Young, because “it is a glimpse into what African American people were producing when they wanted to express themselves, when they wanted to interact and engage, and make something that was an expression of their own humanity.”

In short, says Young, the face vessels were what potters were making “before hours, after hours, and in the in-between spaces of the kilns.”

He believes it is no coincidence that kaolin clay — used as a ritual substance in West Central Africa, but also found in abundance in South Carolina — was used extensively on these face vessels. To underscore this point, the show includes a power figure fashioned by a Kongo West African artist made around 1850.

“That to me is very indicative of what was very likely a rich, spiritual tradition,” says Young.

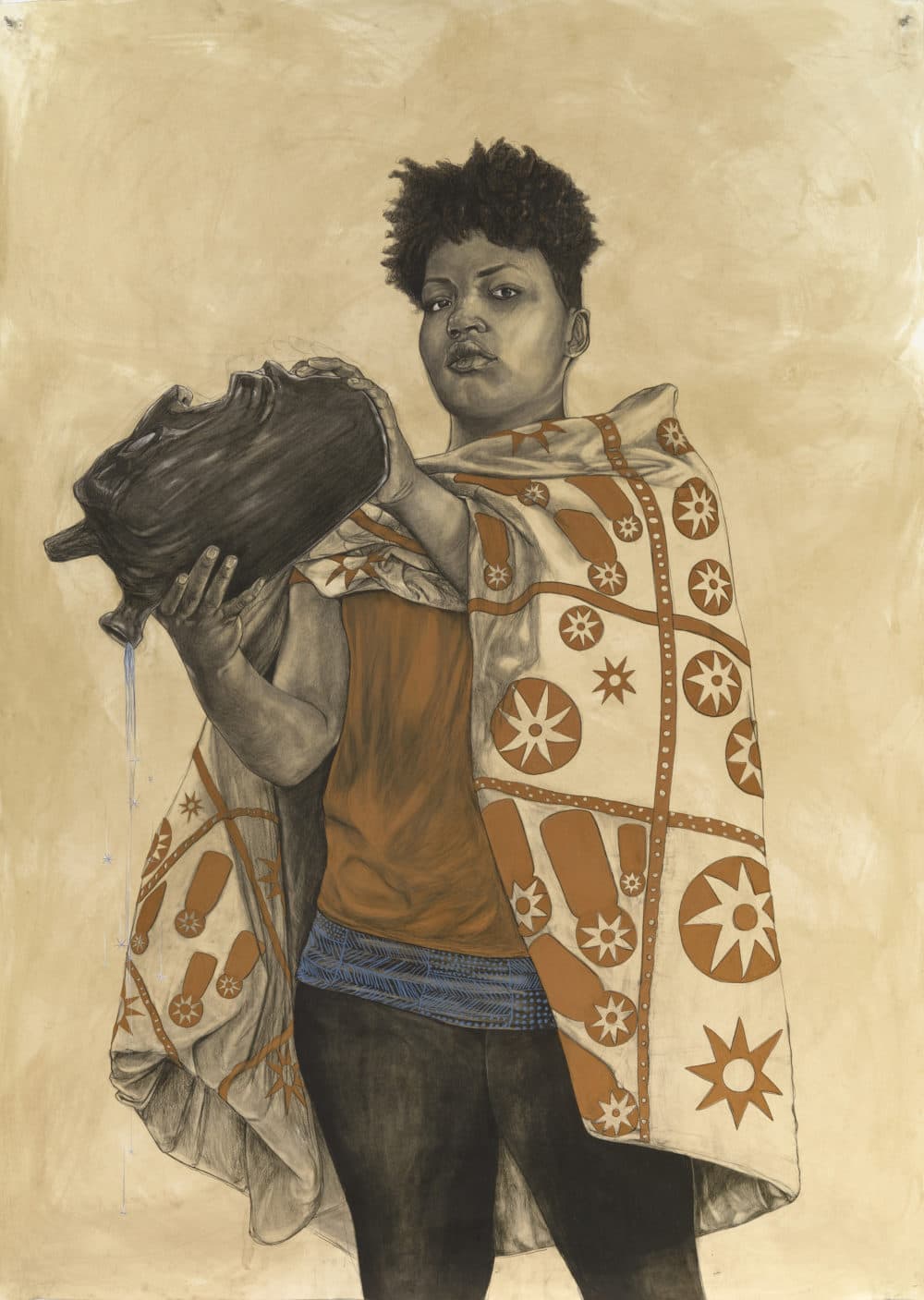

“Hear Me Now” is not content to leave Edgefield pottery to its dark past. It turns out that many contemporary African American artists have found the pottery inspiring. Included in the show are seven pieces by Theaster Gates, Simone Leigh, Adebunmi Gbadebo, Woody De Othello and Robert Pruitt. Leigh, in fact, has produced a whole body of work (not featured in this show) based on Edgefield face vessels.

In “Hear Me Now,” we see one of her pieces, “Jug” of 2022. As the name suggests, the piece is a jug, white, adorned with shapes resembling the cowrie shells used extensively in West Africa religious rituals. The jug feels otherworldly, ethereal, perhaps because of its white color associated with both purity and death in Africa. The shells seem to stand in for abstracted facial features. Woody De Othello’s green-glazed piece, “Applying Pressure” from 2021, is a ceramic piece featuring a hand, a displaced ear and mouth. We have the impression the pot has gotten squeezed, which may be both a historical and present-day metaphor for race relations.

The importance of “Hear Me Now” may lie not just in the survival and revelation of slavery-era objects that many of us knew nothing about, but in what they say about the survival of the human spirit.

“What these objects show is that creativity and artistry can happen and thrive, even under the most brutal conditions,” says Lasser. “There's a humanness to these objects that comes through, even as their makers were living in a world that was dehumanizing them at every turn.”

“ Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina ” is on view at the MFA March 4-July 9 .